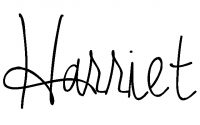

Over the last month or three I have managed to read at least one book (usually more) by or about every one of the women who have sat on the bench for the United States Supreme Court. It has been so fascinating to see how their stories intersect, how they are each unique to themselves, and how they worked together and with their fellow Justices to maintain the Supreme law of the land. In case you’re not up on your Lady Justices: Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, a former Arizona Senator and the first woman on the Supreme Court, she sat on the bench from 1981 – 2006; Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a law professor at both Rutgers and Columbia, and ACLU advocate who has sat on the court since 1993; and Justice Sonia Sotomayor, a Latina from The Bronx who was nominated to the bench in 2009 and is the first Hispanic Justice; Justice Elena Kagan was nominated in 2010 and sworn in later that year, however 5+ years later, there is still only one biography on her, and it’s not very good. Without further ado, the reviews, grouped by Justice, who are listed by seniority on the Court.

Sandra Day O’Connor:

Sandra Day O’Connor: How the First Woman on the Supreme Court Became Its Most Influential Justice, by Joan Biskupic (4 stars). Of the ones I’ve read, this is definitely the best biography on O’Connor. She served as a Supreme Court Justice for 25 years (nominated by Reagan in 1981), often as the swing vote between the four conservative and four liberal Justices (at least, until Clinton was able to nominate a few more liberals, ahem, Ruth Bader Ginsburg). For the youngest and first woman on the Court, her vote counted as the decider in many major cases, starting her very first term. However, what was most interesting to me was to see her opinions and voting change throughout her tenure on the Court. She began as super conservative, but her final two or three years on the court she was a lot more liberal and her reasoning more expansive to protect minorities, women, and other disenfranchised people (including criminals and those being held in military prisons without charge or trial for terrorist activities). I know my own journey towards “woke-ness” has taken some time, starting small and moving outward from there. It’s somehow helpful for me to realize that without being taught from the beginning to, you know, view all people as equal no matter their race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, or economic class, that it truly is a process for us to understand the ramifications to groups of people who are dissimilar to ourselves. O’Connor retired in 2006 to care for her ailing husband, John, who was suffering from Alzheimer’s. I often wonder what would have happened to her voting patterns and her voice had she continued on the Court as a liberal jurist.

The Majesty of the Law: Reflections of a Supreme Court Justice, by Sandra Day O’Connor (4 stars). I had initially thought this was some kind of autobiography, it is not, well, not entirely. There are a few personal stories and anecdotes, but primarily this book is Justice O’Connor detailing the history of the court, the major decisions and docket trends under different Chief Justices, and how the court has maintained and shifted over the last 170 years. Some of the history bits were super fascinating, some were a little dry, however there is a section on women, women’s suffrage, early feminists, and the twisting and frustrating road towards gender equality. I would award that section 8 gold stars if I could! As it was, that section bumped this from 3 stars to 4 stars. I wish Sandra Day O’Connor would write a whole book about feminism and her unique role within gender equality law (from a conservative SCOTUS nominee, to a centrist Justice), I’d be all over that.

Lazy B: Growing Up on a Cattle Ranch in the American Southwest, by Sandra Day O’Connor (2 stars). This memoir about growing up on a large ranch in the dry, dry country of Arizona and New Mexico. This is primarily about ranch life, the cowboys and ranch hands, their backgrounds, talking care of the animals and the land, the struggle of O’Connor’s parents thru their lives to survive and become financially independent. The Day patriarch was tough, stubborn, and unmoving, and there are no apologies for him in this book, just a nodding of heads that “that’s just his way.” Honestly, it’s pretty dry and O’Connor doesn’t give much insight into her future life as a Supreme Court Justice. But, you will learn about life on a massive ranch. So, there’s that.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg:

Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, by Irin Carmen and Shanna Knizhnik (5 stars). The last few years I have become increasingly interested in RBG, this biography was an excellent introduction and overview of her career, her personal life, and some of the monumental decisions over the last 25 years she has been a Supreme Court justice, both ones she agreed with and–most interestingly–the ones where she dissented. I loved reading more about how she fought for gender equality, and how she continues to address sexism and gender discrimination in the United States. Fascinating book!

Raising the Bar: Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the ACLU Women’s Rights Project, by Amy Leigh Campbell and Ruth Bader Ginsburg (4 stars). Not exactly a biography, but also much more than a list of cases and briefs, this short book details the theory and careful strategy of RBG and she layered case upon case to define sexual discrimination and also to outlaw it through policy and statute at the highest court in the United States. Campbell goes through her time at the ACLU and the details of each case, including commentary from RBG’s private papers (housed in the Library of Congress) to show how long-seeing and calculated RBG’s legal arguments were in order to sway an overly conservative court. I knew the basics of most of the cases mentioned in this book, however this is the first place I’ve read so many of the details from correspondence to/from RBG regarding the statue and law, as well as her opinions re: the political climate for women during the 1970’s. Excellent read (and also, a lot of court law and procedure, I had to look up a couple of terms to make sure I was understanding what was going on).

My Own Words, by Ruth Bader Ginsburg (3 stars). I waffled between 3 and 4 stars, this is not the memoir I was hoping for. It is, instead, a collection of writings, briefs, official SCOTUS opinions, and transcripts of speeches from RBG throughout her professional life, with a little biographical information in the chapter headings and a few pages of photos. Some of the writing is fairly dense, official opinions and briefs from the Supreme Court are not exactly light reading. The span of RBG’s career is covered, her work at the ACLU and her methodical and carefully planned assault on gender discrimination laws in the United States. It’s all there, but it is there in very official and professional terms and writing. A few of the speeches and addresses are a little less formal, especially the few excerpts from people who worked with and for RBG, notably her husband who contributes a few fabulous remarks, and President Clinton, who nominated RBG to SCOTUS in 1993.

O’Connor & Ginsburg:

Sisters in Law: How Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg Went to the Supreme Court and Changed the World, by Linda Hirshman (3 stars). The first half of this dual biography keeps O’Connor and Ginsburg’s lives fairly separate, which makes sense. RBG was a professor, then judge, in Washington DC and SOC was a legislator and judge in Arizona. There wasn’t much cross-over of their personal lives, and frankly, their political backgrounds are far from similar. Hirshman clearly likes RBG more than SOC, and that bias shows throughout the book, which is annoying. Hirshman also takes the time to comment on RBGs size (diminutive, petite, tiny, pocket-sized, etc) in almost every chapter, and that got REAL old real fast. Stop it. My favorite chapters in this book were towards the end when RBG and SOC are actually both on the bench, debating over cases and, oftentimes, taking opposing sides. Near the end of SOC’s career as a Justice she started to take her swing vote to the liberal side in several key cases for women’s rights and gender equality, but Hirshman doesn’t spend much time discussing the background of WHY SOC’s swing vote started to swing left.

Sonia Sotomayor:

My Beloved World, by Sonia Sotomayor (4 stars). I really loved this book, learning more about Sotomayor and the pathways and steps she took towards her dream of becoming a federal judge. I love the stylistic differences between a biography and an autobiography, and while a biography may give a wider and more complete picture, the autobiography is the memories of a lived experience, and that is so fascinating to me!

Breaking In: The Rise of Sonia Sotomayor and the Politics of Justice, by Joan Biskupic (3.5 stars). Minus one full star for quoting so much of Sotomayor’s memoir, My Beloved World, during the first half of the book. However, the last third of the book, detailing Sotomayor’s cases and time in the Supreme Court, was fascinating. I doubt a first-person account would go into the kind of back-and-forth and arguments that happened during various cases, and being able to read about those details as well as reactions from other politicians and society at large brought to life some of the race-related cases of the Supreme Court for me. Sotomayor is a proponent of affirmative action and increasing access and opportunity for students of color, and she is not afraid to stand by those opinions even if she is the only dissenting Justice. I loved reading that fire and grit in her personality. I also loved reading about other Latino/as who made advances in politics and through the Judicial system, and the support or not for them and why. Justice Clarence Thomas (SCOTUS) says that the only way to stop discriminating by race is to stop discriminating by race. Sotomayor argues that the only way to stop racial discrimination is to talk widely and openly about the issues, to bring them up constantly and, with enough reminding, the policy makers and the citizens can recognize their own biases and make conscious steps to remove them. After watching so much racial tension over the last few years, I tend to think Sotomayor is correct. Excellent read.

Elena Kagan:

Elena Kagan: A Biography, by Meg Greene (2 stars). In my quest to read a biography or autobiography on each of the women on the Supreme Court this is the *only* book I could find on Elena Kagan. The author repeatedly states that there is very little public information on Kagan, she doesn’t do interviews, and her private papers are still private. With that, this biography does have quite a bit of background information on Kagan, with lots of interviews or statements from people who worked with her in her various positions prior to being a Supreme Court Justice. However, there are also a NUMBER of typos, a couple of instances where Greene gets her facts mixed up a little (stating Kagan graduated from Harvard for her undergrad, despite an entire chapter about her time at Princeton as an undergrad), and in order to fill some pages Greene spends a lot of time discussing New York City real estate, or the career of Justice Thurgood Marshall, or the history of Harvard Law School. Kagan has been a Justice for several years, I am surprised that, to date, this is still the only biography of her.

History of SCOTUS:

Out of Order: Stories from the History of the Supreme Court, by Sandra Day O’Connor (2 stars). I really wanted to love this, but what I hoped would be a dishy book of anecdotes and stories was actually a textbook-like history of the Supreme Court, including personal but not entirely interesting details of almost every Justice who has served on the bench. It was drrryyyyy. Sandra Day O’Connor’s rational, logical, linear brain is on fine display, and I can see how she was an excellent addition to the Court with her super analytical and precise thinking and explaining. However, even in the chapter that began with her talking about how so many people asked her how it was to be the first woman in SCOTUS, she spent less than 5 sentences on herself and instead detailed the “firsts” of all the other Justices, all of them men. Yawn. Unless you are a legal fiend, and/or a SCOTUS history freak, you could probably skip this book entirely.

Other Recommendations:

Madam Secretary: A Memoir, by Madeleine Albright (I love Madeleine Albright SO MUCH! Her story to rise from local political fundraising to Secretary of State is so inspiring!)

Iran Awakening: One Woman’s Journey to Reclaim Her Life and Country, by Shirin Ebadi (The first woman to serve as a judge in Iran prior to the Revolution, this tells her story of becoming a judge, and how her life changed–politically and personally–after the takeover by the anti-judge, anti-woman Islamic Republic.)

For more SCOTUS goodness, here’s my Goodreads shelf on the topic. But, honestly, you’ve just read every review on there, I have not read anything about the male Justices, nor do I intend to do so anytime soon Hashtag: Feminism.