I was really hoping to have a triumphant opening paragraph to this post, with HRC elected as the most powerful leader in the modern world. I will resign myself that she received the most votes for the job (and cross my fingers for the DAMN ELECTORAL COLLEGE), and move forward with stories of women in Ancient Egypt, China, and the Mongolian and Ottoman Empires, women who ruled vast empires in their own right. They are not angels or Madonnas, they are not whores (well, except for Cixi of China, she was literally a concubine…which still isn’t technically a whore), they are politically savvy, militarily ruthless, and multi-faceted humans with enormous decisions to make in order to successfully rule an empire.

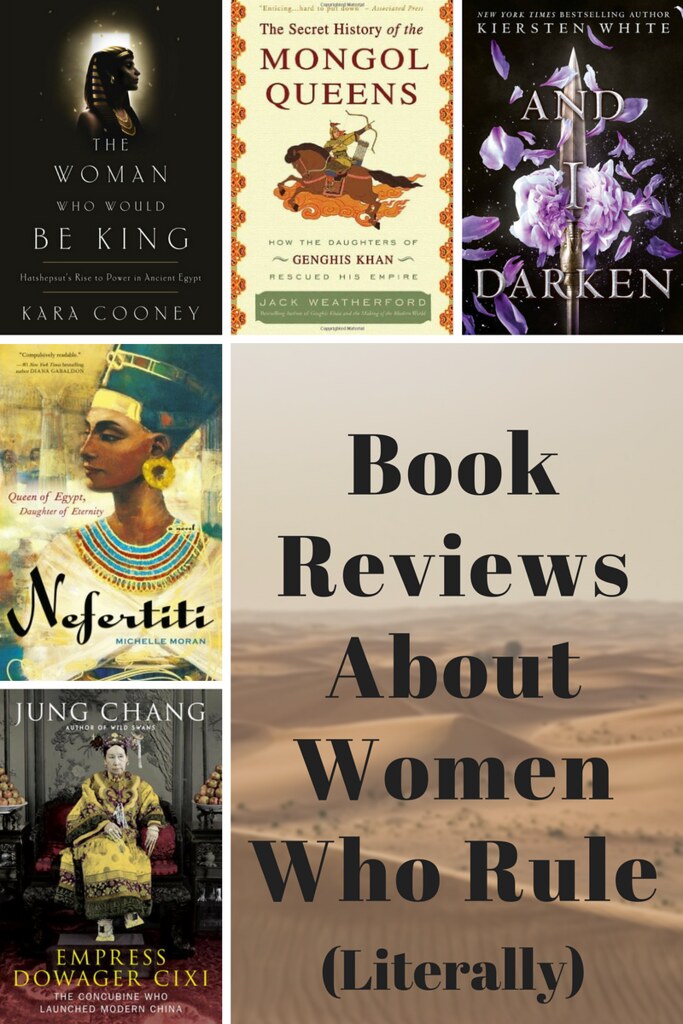

And I Darken, by Kiersten White (4 stars, Historical Fiction). What would happen if someone rewrote the brilliant military mind/historical brute, Vlad the Impaler, as a woman, Lada the Impaler? “And I Darken” would happen. I really loved the mix of Ottoman history, Byzantine history, the clash of Christianity and Islam, sibling relationships, friendships, loyalty to heart and/or country, a bit of romance, and a whole lot of kick-ass female lead. Is Lada perfect? Not at all. But she is interesting in ways most princess-y leads are not. The thing I appreciated the most about Lada is that she felt real, flawed and angry and hopeful and determined in ways I very much relate with on a personal level. She seems like a REAL human with conflicting emotions and internal power struggles with the multiple sides of her own personality; I wish more women were written with that kind of honesty.

The Woman Who Would Be King: Hatshepsut’s Rise to Power in Ancient Egypt, by Kara Cooney (4 stars, Biography). I waffled between three and four stars for this; three because so much of the research is so thin. Frankly, there just isn’t much surviving record of a female Egyptian king born 3500 years ago whose successor tried to erase her from carved memory in temples and monuments (and, subsequently, the text has *a ton* of speculatory sentences and declarations of what “might have” or “must have” or “could have” happened/been thought/been said/etc.); four because 3500 years ago a woman rose to the penultimate seat of power in the ancient world without–as far as we can tell–espionage, war, or killing her husband-brother or nephew-stepson, the male heirs to the throne. Cooney does a good job of constructing a possible story, including a lot of information about life in Egypt prior to the reign of the Pharaohs (which began about 1000 BC). King Hatshepsut (there is no ancient Egyptian word for “Queen”) marked her rule with peace and prosperity, built more temples and monuments than any other Egyptian king except Ramses II, of Moses and the Exodus fame. This was so interesting and I learned so much about Hatshepsut’s kingdom, the rules and ceremonies and rituals in ancient Egyptian courts, heavily tied to religious ceremonies with Ra/Re, the ancient sun god. (Hatsheptsut for President! (Too soon?))

The Secret History of the Mongol Queens, by Jack Weatherford (3 stars, History). There is significant evidence that Genghis Khan’s daughters (and grand daughters, and grand nieces, and so on) ruled with aplomb throughout the vast Mongol Empire that lasted from the early 1200’s to the 16th century across vast tracts of central Asia, China, and Russia, and even as far as Korea. Much of the history of these women was destroyed, literally the pages were cut from the Mongol written record, and only through combing third-party legends and stories can some of their histories be reconstructed. Much of this book focuses on the relationships of those women with their husbands, sons, in-laws, and nephews throughout the generations of Mongol rule, there is actually probably more about the male Mongol warriors and rulers than the women in this book. The last quarter focuses on one warrior Queen, Mandhuhai, who brought the Mongol Empire back to life, literally, by placing a crippled child, the only surviving male heir of Genghis Khan, on the throne and then spending the rest of her life protecting and raising him to be a strong Khan, ruling by his side for almost 40 years. Throughout the former realms of the Mongol lands there are dozens of legends and stories of Mandhuhai, and by actually–gasp–paying attention to those stories Weatherford was able to construct a relatively stable timeline of her life. (His “afterward” states repeatedly that he dismissed all of the stories about Mongol women while he was doing years of research for a book about Genghis Khan…which makes me SERIOUSLY question his viability as a historian, anthropologist, or researcher. “It’s cool, I’ll just ignore HALF of the population of this empire completely because they have lady parts and, therefore, are less important than the penis wielders.” Ugh.)

Empress Dowager CiXi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China, by Jung Chang (3 stars, Biography). This is an exhaustive biography of the last Empress of China, Cixi (tsi-shee) who ruled from 1861 thru 1908, opening China to western trade and western influence, putting down internal rebellions and political unrest, dealing with the Opium Wars and the Boxer Rebellion, all the while maintaining absolute power on the throne of China. The author tends to paint her through rose colored glasses, glossing over some truly heinous decisions and rule (like, poisoning her nephew, the budding Emperor, and drowning his wife in a well, and ignoring brutal religious conflict, etc etc etc) and focusing instead on her legitimate successes. In addition to detailing the life and political (and personal) decisions over her long life (she died when she was 73), Chang also explains some major historical landmarks in China and the western colonizing bastards, oh, I mean, powers, that shaped much of the subsequent conflicts between Britain, Russia, Japan, France, etc., etc., etc.

Nefertiti, by Michelle Moran (2 stars, Historical Fiction). Within a few pages it became very clear to me that this was romanticized historical fiction, a few chapters in it was clear that it was MEHstorical fiction. The book is told from the point of view of Nefertiti’s half-sister, the one who follows her to the palace and is expected to give up her entire life, all hopes and wants and dreams to the whims of her ever-more-histronic ruling lady. Nefertiti’s character, sadly, is never really fleshed out more than face value: she is portrayed as a stunningly beautiful but completely selfish woman with no real connection to the people, except that she’s beautiful and throws money at them, despite destroying their gods and forcing them into slavery to build her a new city to a new god. I’m annoyed. Moran routinely mentions Hapshepsut, a ruling pharaoh in her own right, as someone Nefertiti tries to model herself after, but she a) doesn’t really explain anything more about Hatshepsut except that she was pharaoh, and b) Nefertiti as portrayed in this book never has enough support or power to truly reign in her own right, she’s not given strength and political savvy, she is a beautiful puppet. Because, of course, why would a woman (in the ancient world or now) be able to rule on her own. (Insert MUCH GRUMBLING and CURSING here over the damn, pervasive Patriarchy.)

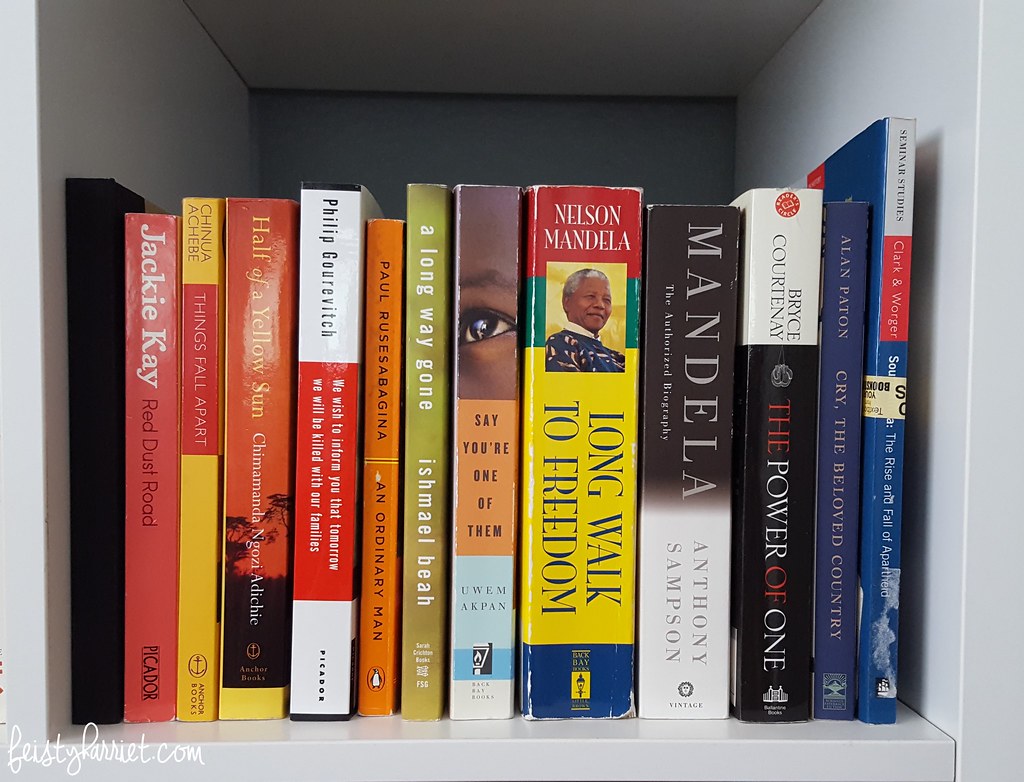

More books about women who rule.