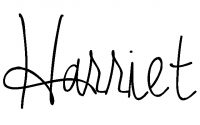

I have a thing with learning more about how the brain works,. I love reading books about weird medical industry outliers, and I love reading neuroscience stuff about how neurons fire and misfire and are mapped and re-maped, and I love love LOVE when the an author can write about how and when the right brain and left brain come together (see: Proust review below). It’s hard to find a really engaging armchair neuroscience book, and I’m not saying that one of the following six is that book, but you will most likely enjoy one of the first three.

(Unless you’re a psychopath, the only read The Psychopath Inside, and start a club with author James Fallon (nope, not Jim, James) because he’s kind of a psychopath too. Oh, sorry, should have given a pre-emptive “spoiler alert!” there. My bad.)

The World’s Strongest Librarian: A Memoir of Tourette’s, Faith, Strength, and the Power of Family, by Josh Hanagarne (5 stars). I loved this book in every way. Hanagarne’s love of books, his struggles with Tourette’s, his thoughts about family and faith. This felt so real, so honest, and so completely refreshing, despite having some truly difficult pieces about Tourette’s and the causes, treatment options, and prognosis. Hanagarne works in my home library, the main branch of the Salt Lake City library, and he discusses lecture series that I actually attended and describes the glorious architecture, AND IT IS STUNNING! All sky-high windows and open spaces and modern sculpture, it’s one of my favorite places downtown. So, immediately I loved this book more than I probably should have (after 2 pages) because of the location in my heart-home. However, I also deeply appreciate Hanagarne’s respect for his faith, but also his hefty dose of reality about it. The Mormon church has some truly beautiful doctrine (that is not in the very famous, bawdy musical), but there is also a lot of weird cultural stuff, some tied to doctrine, some that isn’t but is pervasive in Mormon areas. It’s a tricky line to walk, but he handles it perfectly without lampooning the church or the faithful, and without trying to convert the reader. (I had zero idea going in that the author worked in one of my favorite buildings or that he was Mormon, and his love for my home and his treatment of my religion was such a delightful surprise and certainly contributed to how much I loved this book.) Hanagarne focuses on his Tourette’s diagnosis and how it affects his life, some of the treatments options he tried, ranging from truly bizarre to extra scientific, and the ways he learned to deal with repetitive short-circuiting of his brain. (Technically this book is more memoir than scientific brain treatise, but my blog, my rules, so whatever.)

Proust was a Neuroscientist, by Jonah Lehrer (5 stars). I have wanted a book like this for a VERY long time, Lehrer writes eight essays about groundbreaking artists and their work as it is reflected in neurology principles, most of which weren’t discovered and principle-ized until well after the artist’s work was published (and, more likely, the artist was long dead and gone). He discusses four novelists and their topics of writing (Walt Whitman, feeling; George Eliot, freedom; Marcel Proust, memory; and Virginia Woolf, self) and how each of those topics have direct neurological roots that Whitman, Eliot, Proust and Woolf clearly define and explain long before scientists discovered the proof. The other four chapters discuss similar principles of how we as a consumer experience art (Auguste Escoffier’s amazing epicurean creations; Paul Cezanne’s use of color and form and light; Igor Stravinsky’s music; and Gertrude Stein’s use of language) and then goes on to define the neurological process that allows us to enjoy and crave umami, or how a Stravinksy symphony affects our brain differently than Wagner or Beethoven. This bridge of art and science was glorious in every way and I think I must own this book to flip back through my favorite sections again and again.

Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World, by Cal Newport (4 stars). For the most part, I really loved this. I think Newport has a lot of really great suggestions and research. His rant about social media got me a little “meh”…never does he provide as an option the idea that you limit your social media consumption through a specific strategy, it’s either all-consuming or you delete your accounts. So, that was annoying. (Example: I log out of all social media apps when I’m done scrolling so I never receive notifications to distract me. Is it a pain to have to sign in? Not really, it takes 2 seconds. Not receiving push notifications from Twitter/Instagram/Facebook/Whatever has GREATLY reduced my attachment to and time wasting through social media. Win-win.

Hallucinations, by Oliver Sacks (3 stars). I like Oliver Sacks, his book “The Man Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat” was pretty great; but this book is….it’s meh. He seems to prance over some of the deeper causes of hallucinations, he refers to larger segments he’s written about this case or that patient or this syndrome/disease/whatever in another book–he seriously cross references his own books a TON–and his definition of hallucinations ranges from drug or alcohol-induced episodes, to concussions, to allergic reactions, to legitimate deeply rooted psychological issues, to nightmares and PTSD. It’s…it’s just too broad without enough deep science to back it up. Not my fave.

Smarter: The New Science of Building Brain Power, by Dan Hurley (3 stars). This was okay, but not great. The basic premise surrounds whether or not there are activities or exercises we can do to strengthen our brains and make us smarter. The short answer: yes, to a degree. Things that make your brain run smoother and faster can increase it’s capacity: listening to classical music stimulates neurons, but only a little. Getting enough sleep and plenty of exercise strengthens your neuro-network, but only a little. Brain-stimulating puzzles and play can increase your capacity, but only a little. In combination, you may be able to increase your brain power a little bit, but only by a few IQ points. Now. If you have had some kind of brain trauma there is a lot more room for improvement, healing, and growth, but no one wants to wish crippling brain trauma on a person in order to prove “get smart quick” schemes.

The Psychopath Inside: A Neuroscientist’s Personal Journey into the Dark Side of the Brain, by James Fallon (2 stars). The first two thirds of this book I quite enjoyed, I mean, it’s an interesting twist to have an actual psychopathic neuroscientist (who is in denial about his psychopathic brain) be writing a book about psychopaths and their behavior. The last third, however, Fallon begins to really drill down into his own behavior and psychopathic tendencies, his mania and relationship patterns….and, he’s a SUPER ass. Writing a memoir reflecting on all those things makes him more of an ass, not less of one. It was almost unreadable, to be honest. If you’re looking for a better book about psychopaths, I’d recommend Jon Ronson’s “The Psychopath Test” instead.

Other Brainy Recommendations:

- The Psychopath Test, by Jon Ronson

- Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain, by David Eagleman

- A Whole New Mind: Why Right-Brainers Will Rule the Future, by Daniel Pink

- The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains, by Nicholas Carr

More books about brains and neuroscience.

All book review posts on ye olde blog(e).